IL VERONESE AND GIORGIONE IN CONCERTO: DIEGO ORTIZ IN VENICE.

Manuel Lafarga, Teresa Cháfer, Natividad Navalón & Javier Alejano

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLA DE CONTENIDOS

Quaerendo invenietis.

Seek and ye shall find.

Buscando encontrarás.

J.S. Bach to Frederick II of Prussia in the Musical Offering dedication.

J.S. Bach a Federico II de Prusia en la dedicatoria de la Ofrenda Musical.

El Pitor venezian, musico esperto

Ben suona un istrumento e ben l'acorda,

E se pur falsa el toca qualche corda,

L'intende dar più gracia a quel concerto

Un con man regolà, pratica e scaltra,

Forme fughe, passazi, bizarie

Tocade, recercari, fantasie,

E fa trasporti da una chiave a I'altra.

L'altro no sa sonar senza la carta,

E va cercando i taste a deo per deo;

E con muodo mecanico e plebeo

Vuol far cadencia, e strupia terza e quarta ... [1]

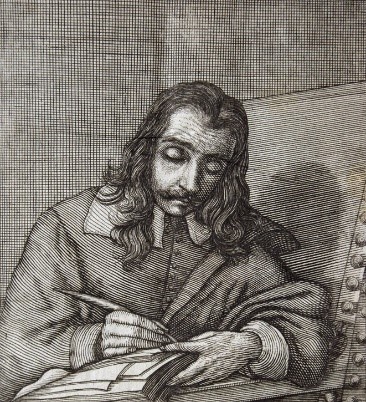

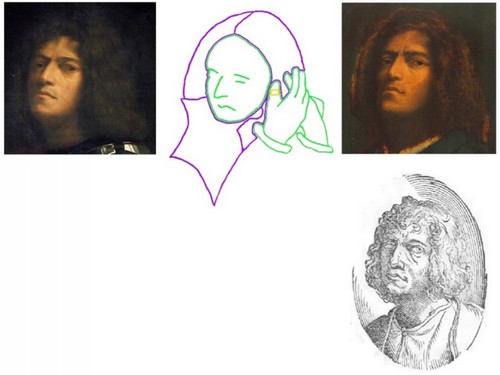

Figure 1. Marco Boschini (1660).

Figura 1. Marco Boschini (1660).

Figura 1. Marco Boschini (1660).

RESUMEN

El presente ensayo propone que el músico español Diego Ortiz está retratado en el famoso lienzo manierista Las Bodas de Caná de Paolo Caliari, concretamente en el rostro del personaje que parece hablar al oído del autorretrato del propio Veronese, en tanto director de un conjunto de violas da gamba. Conjeturamos que el autor representa al músico como uno de los mayores exponentes contemporáneos de este instrumento. Nuestras propuestas y conclusiones están basadas en los pocos datos biográficos existentes, en el grabado que le retrata en su propio tratado, y en el retrato que proponemos suyo en la obra de Veronese, junto con los repetidos y hasta ahora infructuosos intentos en la literatura para aclarar la identidad de este personaje. Proponemos igualmente una identificación razonada para el rostro que ocupaba el lugar de Ortiz en el diseño original, el pintor veneciano ya fallecido Giorgio de Castelfranco, también llamado Giorgione, el cual fue sustituido por el de Diego durante la realización de la obra.

ABSTRACT

This first essay proposes and documents the presence of the Spanish musician Diego Ortiz in Paolo Veronese’s famous mannerist picture The Wedding at Cana. Specifically, we suggest that he is the person who seems to be making comments to Veronese, as the conductor of a viola da gamba ensemble.

Presumably, the author of the picture represents the musician as one of the most significant contemporary exponents of this instrument.

We derive our proposals and conclusions from the few available biographical data of Diego Ortiz, his portraits in his treatise and in Veronesne’s canvas, and from an analysis of the repeated and unsuccessful trials in the literature to identify this personage.

We also suggest that the Venetian painter Giorgio da Castelfranco (named Giorgione), was represented in the initial design of the painting at the position of Ortiz and then painted over.

Preface

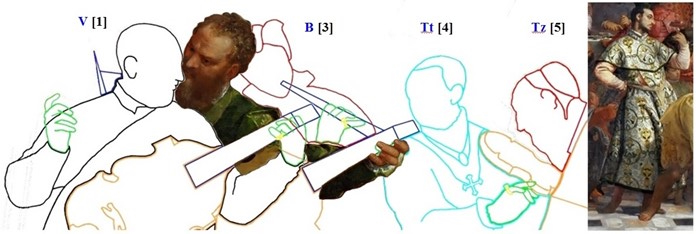

The Paolo Caliari ‘s canvas Wedding at Cana was initiated on June 1562 and delivered on October 1563 to its owners, the Benedictine monks of San Giorgio Maggiore of Venice. It was a posthumous tribute to Giorgio de Castelfranco, named Giorgione, from its beginnings until near its completion. Giorgione, who was dead 50 years earlier, is at present considered the founder of the so-called “Venetian Painting School”.

The design and composition of the consort which constitutes the central scene of the opus suffered a certain number of important sequential re-arrangements until to conform the actual visible ensemble in the completed picture. Here, a new very relevant international personage in the contemporary musical environment was placed on top of the absent Venetian master.

It is very probable that the famous Spanish violagambist Diego Ortiz ― the chapel master at the Court of Naples from the 1550s to his death in 1570 ― visited the city during the last months of the canvas elaboration. The reason would be the future edition of his second book in Venice by the editor Antonio Gardano, published in 1565, a few more than one year later to the completion of the painting work.

We conjecture that he was a visual model to Veronese for his own portrait at the canvas during his stay at the city, replacing definitely Giorgione and finally transforming the instrumental ensemble in a consort of violas da gamba.

However, his emergence in the definitive scene represents only the last of the transformations which were operated by Paolo Caliari on his design: all the previous rearrangements had been motivated by reasons which were alien to the undoubted relevance of the Neapolitan master in the contemporary musical international environment.

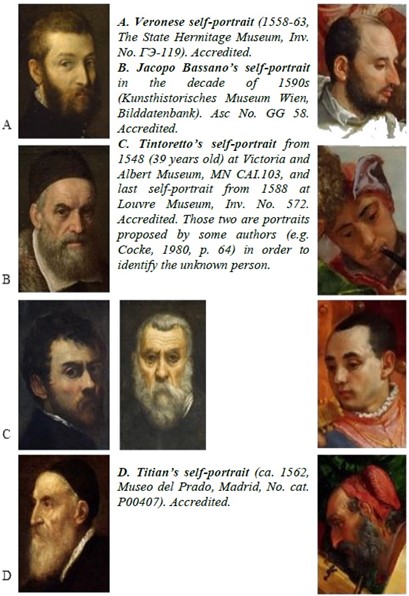

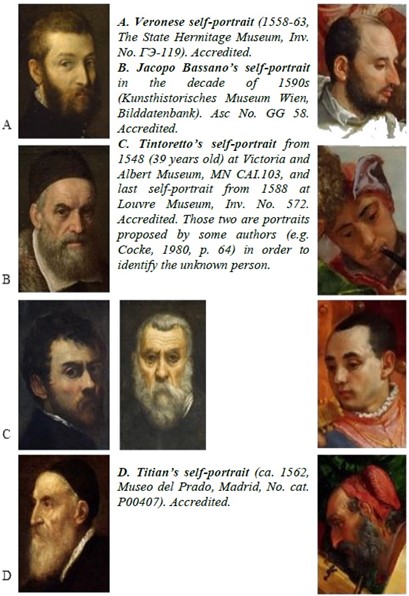

From Antonio Zanetti the Younger ‘s (1754-1812) reinterpretation of scholar tradition in 1771 ― “si crede con ragione che sia dipinto Jacopo Tintoretto” (sic.) [2] ―, the identification of the person who seems be whispering to Veronese ‘s ear, and holds a very similar instrument to the Paolo ‘s one, has induced to many confusion in the literature to our days.

To this moment, any other author referred to the unknown who occupied the place of Giorgione. Those who had referred to the identity of the musician-painters followed the Boschini ‘s tradition in 1674, who identified Tintoretto not as our bearded Neapolitan but as the violinist.

Authors who have wished make mention to our protagonists, from the second Zanetti ‘s non-proved new proposal [3] , can be grouped in two groups: those who identify the violagambist as Tintoretto with no mention of the violinist, and those who avoid to refer to the unknown behind Veronese. A more imprecise third group of authors makes reference to only some personages with no mention on others, both related to the musician-painters as instruments.

Our interpretation on the identity of all the musicians in the scene is the first reasoned one in the literature.

In addition, it is also congruent with that of Moriani, who had finally identified in a correct way all the instruments along with their respective performers. So, he alludes to our protagonist as an unknown person, from who he only says that “Seminascosti, dietro di lui, ci sono altri due musici: uno con la viola da gamba e l’ altro col trombone” (sic.) [4].

The Boschini ‘s original proposal has been labeled as a kind of “legend” among others, as a consequence of the suddenly fame of the canvas from its completion to our times.

However surprisingly, the actual legend at the monastery one century later its completion [5] asserted that there were, besides the author “… le Giorgione, le Tintorett, et le vieux Bassan” (sic.) [6].

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, minister of Louis XIV of France, who had recently visited the Venetian island in 1641, registered the story when came back to his own country three months later, in the relation of his travels through the contemporary Italia. In an obvious way, the legend was narrated to him by the religious authorities of the monastery, and it can only proceed from those who had watched to the painting before its completion one century earlier.

The relevance of Giorgione at Venice in the 1500s is doubtless: he was schoolfellow (perhaps also master) with Tiziano Vecellio in their youth, at the Bellini ‘s workshop and later in some of the works which were accomplished by Giorgione during his brief pictorial activity, concentrated in a few more than one decade at the beginnings of 15th-century.

In 1508, Giorgione had conducted the restoration of Fondaco dei Tedeschi ‘s facades, the building of the German traders, one of the biggest and more emblematic buildings of Venice. He made the work with entire freedom on issues and figures, however the enterprise ended with no agree by the painter. He finally transferred the completion of the comission to an expert triunvirate under the supervision of Giovanni Bellini.

Giorgione was a renowned, admired, “imitated” and venerated by several generations of Italian painters during the Cinquecento. He is considered the first innovator in many techniques and features which defined onwards to the Venetian renacentist painters. He is likely considered as the first innovator on certain pictorial genres as the portraiture, the feminine nakedness, the treatment of landscapes, and equally on the small pictures for contemporary conneiseurs and collectionists.

1. The “Etruscan Devil” of Mannerism and the Golden Ring

Il Veronese was a disciple of the doctrine that design and composition are the inescapable basis for an elegant, refined and intellectual painting [7] , and his initial work until 1555 is known as that of “the Etruscan devil of mannerism” [8]. This aesthetic stream had one of its main pictorial centres in Venice, and Giorgione [9] , Titian (Veronese’s teacher), Veronese himself, and the other painters in the work we will deal with, played a decisive role.

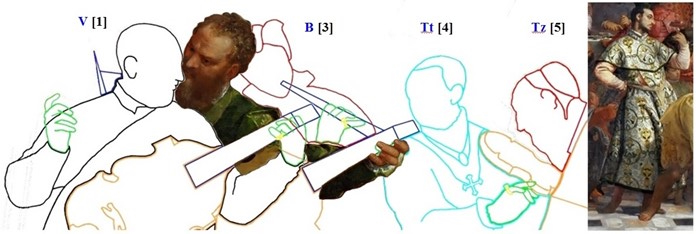

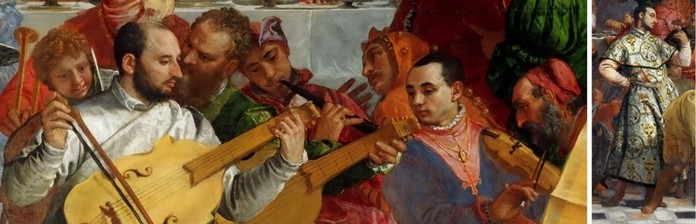

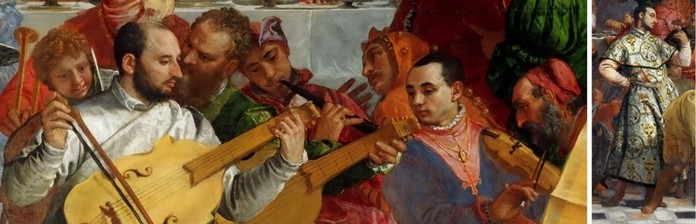

Figure 2. The musical consort (4 painters plus Ortiz). Louvre, Inv. 142.

Among other techniques, the new style replaced or coded elements in the works through the inclusion of contemporary or tradition-consecrated personalities or symbols. This practice was rejected by inquisitors but enjoyed a huge boom among Protestant humanists and in those courts and republics that were outside the influence of the Holy Office, like in Venice.

Paolo himself used mannerism as a resource to bring painting close to the concept of liberal arts, a status which was already achieved by music [10] : the new techniques allowed him to escape from mechanical (imitative) criterion which was attributed until his time to pictorial reproduction as a mere copy of reality. This was probably one of the primary ideals which he defended in The Wedding at Cana through the mixing of two groups of artists, musicians and painters.

The many “suppers” and similar situations painted by Veronese and his Venetian colleagues represented certain biblical tales as genuine celebrations in the prosperous city of his epoch, and Paolo included a self-portrait and representations of the leading coeval painters of the Venetian School on this canvas, identifying all them with a golden ring on their little fingers.

2. A valuable order with important people

Paolo received the commission for the Wedding at Cana from the Benedictine monks from the Basilica of Saint Giorgio Maggiore in Venice. The painting was of significant dimensions (994 cm x 677 cm) and had to decorate a wall of 66 m2 of a room recently reconstructed by Palladio [11] , who got the contract for him. The completion of the opus took him fifteen months with the probable assistance of his brother.

The work represents the first miracle of Jesus in which he transformed water into wine at a Galilean wedding. None of the depicted characters is speaking or conversing because of a monastery rule ― to be silent while eating in the refectory [12].

The convent was frequently visited by important guests and artists, and its refectory was included in guides and travel books of contemporary Venice. Therefore, the desire of the monks was to express through the painting also the power and richness of the monastery, one of the most important at that time [13]. Many of the personages who appear in the painting are from high society, some of them of international relevance including monarchs and emperors [14].

Figure 3. Ortiz and the whole Golden Circle (including Benedetto Caliari, Veronese’s brother, standing on the right side).

The contract specified certain requirements, like that the largest possible number of characters should be included and that high-quality colours and pigments containing precious minerals should be used. During the following decade, the workshops of the four musician-painters represented on the canvas produced numerous similar works for the refectories of Venetian monasteries [15].

The painting became so famous that many approached the city to contemplate it. European princes and rulers repeatedly asked for copies, and many painters and sculptors came to San Giorgio only to ask the monks for permission to reproduce the painting. This went so far that on December 17th, 1705, the monks decided not to grant any further permits [16].

3. A string quartet and an instructor for viola da gamba

The character of Jesus Christ appears as usual in the geometrical centre of the composition [17], though as a secondary figure behind the group of musicians. The presupposed protagonists of the event, the married couple, appear sitting at the left corner of the picture. The central area is composed of a consort of four violas da gamba: the self-portrayed author (V) and an unknown person behind him, both apparently playing violas tenor, and two other famous contemporary painters, Tintoretto (Tt) and Titian (Tz) playing soprano and bass viola [18].

Bassano, another famous painter (B), appears between Tintoretto and the unknown person playing an instrument usually referred to in the literature as a flute, however it is a cornetto almost without curvature (which can clearly be appreciated by the mouthpiece on his lips) [19]. The person standing behind Titian is the painter’s brother.

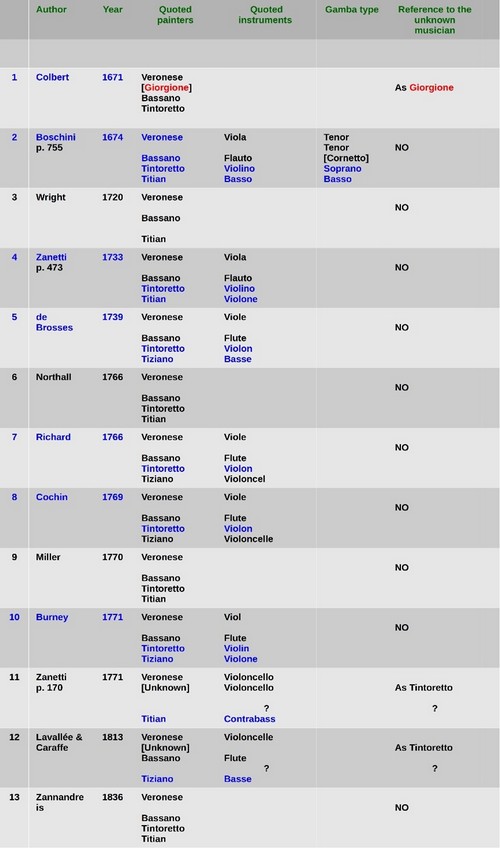

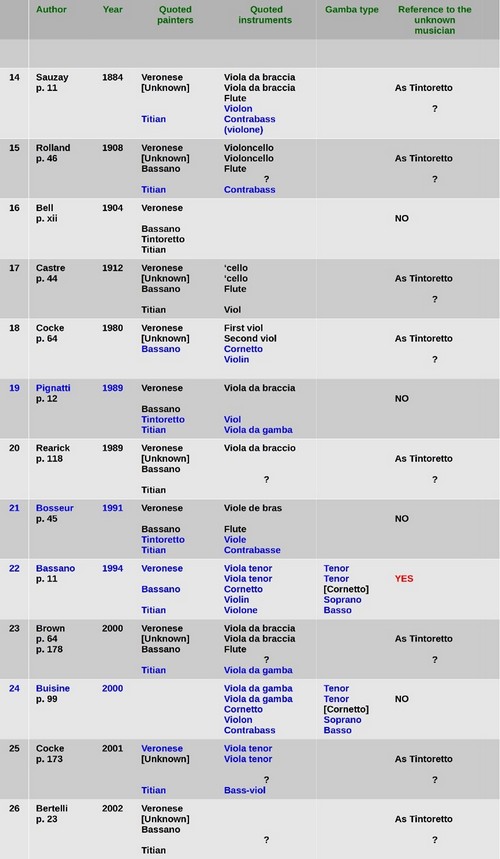

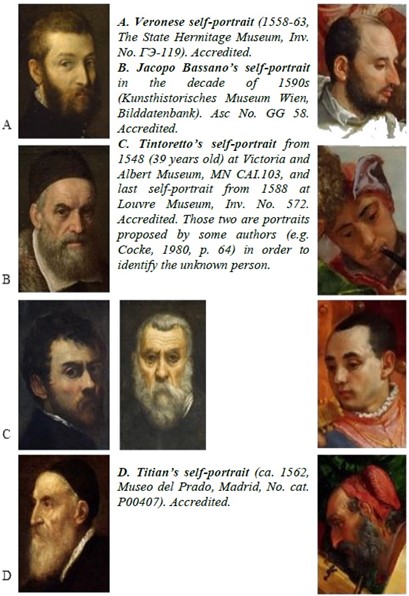

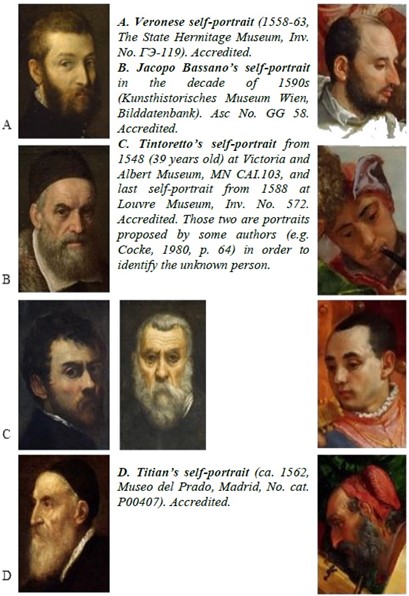

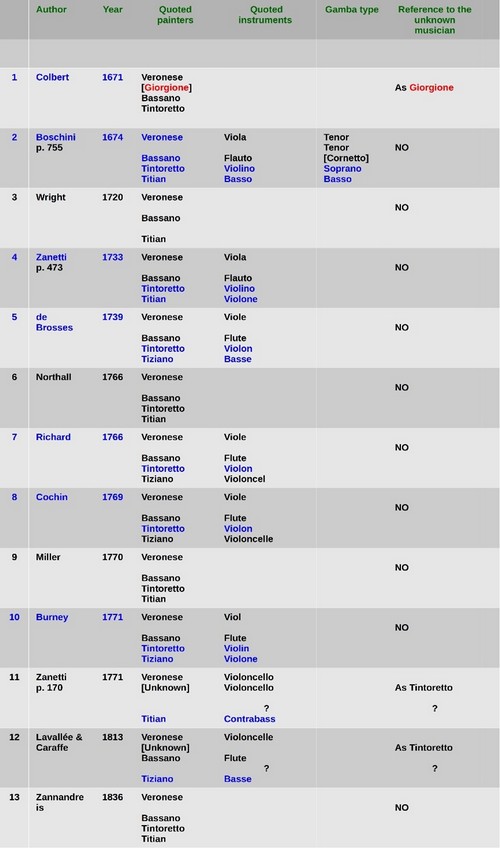

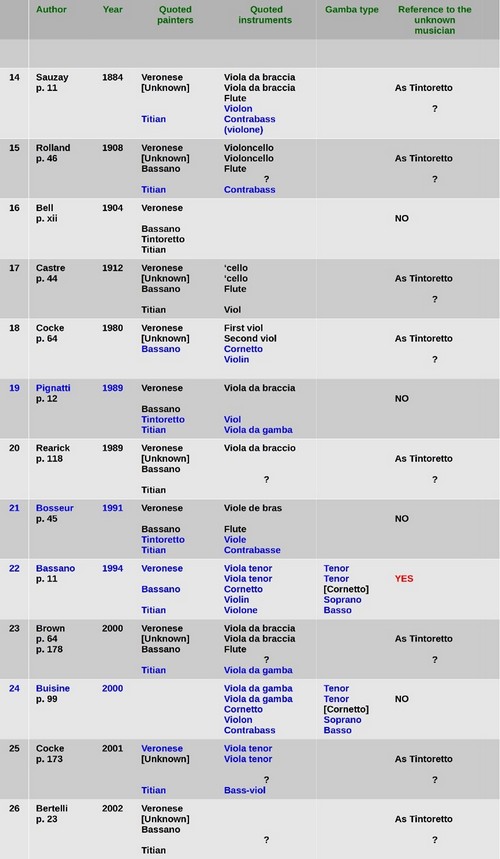

Including the recent study of Moriani (see below), there are at least thirty relevant authors in the disciplines of art and biography who refer to the identity of the musicians (see Table). It turns out that many of them make erroneous ascriptions (also to instruments) and none identifies the unknown person, although some refer to him as perhaps being Tintoretto, alluding to a certain resemblance (wrongly, in our opinion, as we will equally show in Figure 8).

Figure 4. The Golden Ring (5 painters), and the quintet (consort) with Ortiz.

The silhouette does not show the two golden rings of Titian, nor on Benedetto’s little finger (on the right).

Figure 5. The Wedding of Cana. Detail of the viola consort and the cornettist (Bassano).

The identification of the central characters (four painters and one unknown person) is based on Marco Boschini’s work: he identified the quartet of painters ― not that of viola players; here Bassano is included ― as the “Golden Circle” based on the ring which they have on the little fingers (here Benedetto is included) [20].

However, the critical fact for us is that he does not mention the unknown musician behind Veronese, who does not wear any ring.

It could be argued that the position of his hand over the neck of the instrument does not allow an adequate judgement about whether he wears a ring or not. But we conjecture that the author had the opportunity to represent it if this had been his intention ― as he did with his brother, who also was a painter (standing at the right: Figures 4-5). It can be appreciated that it would be perfectly visible on his left little finger.

Two centuries later, Zanetti the Younger (1771) proposed a new unproven theory [21] which postulates the unknown person as Tintoretto. However, he omitted the violin and the cornetto: Zanetti says that he believes “to recognize with reason to Jacopo Tintoretto” (sic.) in the character next to Veronese [22]. Nevertheless, five of the nine authors who previously referred to the musicians identified Tintoretto as the violinist, and none of them mentioned the unknown person [23].

In a recent study, Ton comments Boschini’s proposal of 1674 as “unfounded” (sic., p. 32), suggesting that it was not an original idea but an even earlier “tradition” of legends which increased the aura of the picture, and adducing that it had been recorded in 1671 by Jean-Baptiste Colbert.

Surprisingly, and just after visit San Giorgio’s refectory, Colbert said that Paolo was accompanied by “le Giorgione, le Tintorett, et le vieux Bassan” (sic.) [24].

Zanetti ‘s new proposal was later endorsed by Sauzay [25], Rolland [26], and others with the same frequently repeated mistakes in the ensuing literature [27]. Many of them have referred to only four players ― including Veronese ― often omitting the “violinist” [28].

Pignatti, e.g., lists some musicians and instruments correctly from right to left (including Tintoretto: “viola”), however he does not mention the unknown character and confuses Paolo’s instrument, which he takes to be a “viola da braccio” [29] . Rearick quotes Zanetti’s opinion and lists them seemingly from right to left with no allusion to the respective instruments, however repeating the confusion with Veronese’s instrument [30]. As Pignatti, Bosseur correctly assigned the instruments to their corresponding characters, however he still calls the cornetto a “flûte” and the tenor viola a “viola da braccia”, without mentioning the unknown character [31].

Hanson also describes four musicians in the same inaccurate way, and she says again that both Veronese and Tintoretto play “viola da braccio” (sic.) [32]. However, this appreciation is technically incorrect, as only the second (the violinist) does play a viola da braccio, while Veronese is playing an instrument near identical to the unknown ‘s one ― a viola da gamba (which she in turn correctly assigns to Titian) [33].

Dardel identifies the same individuals in a similar way [34]. We must add two qualifications here. Firstly, the instruments of Veronese and the unknown are tenor viola and melodic bass respectively, while that of Titian is a bass viola [35]. And secondly, the performance style to hold the tenor viola in a horizontal position and not between the legs, as actual players do and the qualifier “gamba” indicates, was a “vihuelistic” technique that precisely Ortiz (1553) advocated [36].

Other works persevere in the same claims, remarking that the violin player cannot be identified [37]. However Boschini was the first to correctly attribute this character to the violinist, Bertelli names again only four musicians from right to left omitting this performer, and assuming that the unknown is Tintoretto “according to Boschini’s tradition” (sic.) [38].

Others have recovered the second Zanetti’s proposal asserting that Tintoretto is more like our unknown person through the comparison with two self-portraits (Figure 8C) [39] ― an opinion that we evidently cannot share.

Viallon, e.g., also correctly names the instruments, however is wrong about Tintoretto’s identity [40].

Bassano is the first to properly name all of them, although he does not make assertions about Tintoretto’s nor unknown person’s identity [41]. Buisine seems to be the second, however he also avoids the musicians [42].

Zirpolo mentions only three musicians, with no order and no reference to Tintoretto nor the unknown: “… There are portraits (from left to right) of the artist Jacopo Bassano, Veronese himself, and Titian” (sic.) [43]. Bätschmann even identified the violinist as Benedetto Caliari [44].

Finally, a recent monograph dedicated to the Veronese’s suppers list all musicians and their instruments in the same way as we have presented here, referring to the unknown person as a non identified one [45].

Many Renaissance artists and intellectuals were interested and quite proficient in other disciplines, mainly in music and specially in Venice [46].

Titian received an organ as payment for the portrait of instrument maker Alessandro Trasuntino [47]. Tintoretto was probably a competent musician since his youth [48]. Veronese was an enthusiast amateur musician: he designed the whole external organ complex for the church of Saint Sebastiano in 1558, and simultaneously also the plans of a new one for that of Saint Geminiano at Saint Marcos square [49]. Giorgione was a skilled singer and lute player [50].

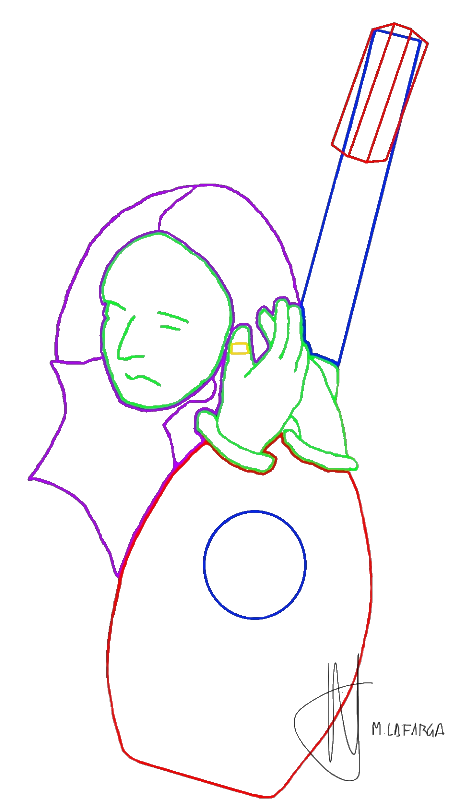

Let’s focus now on the unknown character just next to Veronese, assuming he played a relevant role. In 1992, an analysis by X-ray techniques showed that he was not present in a former original version [51]. This fact gives support to the assumption that he could have been added a posteriori (but before termination) because of Ortiz’ reputation with the viola, and because he was probably the instructor of some contemporary influential celebrities [52].

This character is looking at Paolo and not at his own score as the rest of musicians do [53], and he exhibits a gesture of verbal instruction (which seems to break the Benedictine silence rule) very close to Veronese’s ear.

It would be incoherent to assume that this character is an anonymous musician, given his attitude and the circle of very famous painters who are also musicians. However, the absence of a ring on his finger and the fact that he was not in the initial design explicitly exclude him from the group of painters. But the most probable assumption is that he was a professional musician, someone relevant in his distinctive features within the quintet: an important viola-gambist.

We have pointed out before how the aesthetic project of Veronese ― to establish painting as a liberal art ― had already been accomplished by the musicians. The emblematic character of Ortiz most likely represents those musicians in opposition to the painters who were music-enthusiasts.

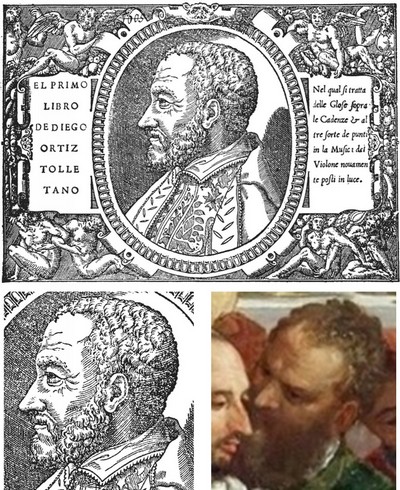

4. A surprising resemblance: Twelve coincident facial features

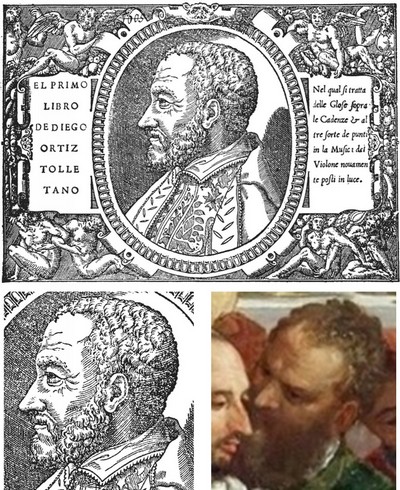

The well-known practice of printers to use occasionally a similar design to illustrate the covers of different books is not a decisive objection to claim that the portrait of the Ortiz’ treatise (1553) is authentic: no other use of this specific one in other books is known. The authenticity of the engraving is corroborated by the prestige of the publishers, who were the official type-printers at the Accademia Romana [54].

The Dorico brothers were specialized in printing musical works of renowned authors from 1539 to 1555, circumstance which concede validity to their representations of the features of important characters in engravings. The engraving is also the only known portrait of one the most important and famous European violagambists at the moment of publication of the treatise (ten years before the termination of the Wedding).

His facial features are quite unusual: though individually or in some combination they could be present in many other characters, it is unlikely they all appear together at time in two different famous violagambists separated by ten years. It is also unlikely that other specialized coeval musicians could coincide in so many traits.

Figure 6. Detail of the unknown musician compared to Ortiz’ portrait on the cover of his treatise.

We think that the general shape and aspect of the face and hair of both portraits show a surprising similarity, which is supported by twelve specific features:

- shape of the hairstyle;

- hair type: short and curly;

- shape and density of the beard;

- shape of the receding hairline at the forehead;

- form of the hairline plus one wrinkle at the temple;

- three longitudinal wrinkles in the forehead;

- three wrinkles in the corner of the eye;

- prolonged pocket below the eye;

- general shape, contour and size of the nose;

- shape of the ala and alar furrow of the nose;

- shape of the ear and its relative size;

- proportions of facial traits and general overall appearance.

In addition, the “violinist” (Tintoretto, Figure 8C), who seems to be very much younger than the unknown, was 44 years old when the canvas was finished, while Diego was 53. With our interpretation, the ages fit better with the facial features for each individual and in relation to each other.

5. Further support: Seven chained arguments

Various other arguments concede credibility to our main hypothesis, in addition to the golden rings identifying the painters and the mentioned resemblance.

- The relevance of Ortiz as a contemporary musician was enormous: he was one of the most representative figures of performative instrumental art with violas da gamba and Maestro of the Royal Chapel of Naples, one of the most important Renaissance ensembles, during more than a decade [55]. It is then coherent to suppose that Veronese decided to include the maestro playing the tenor viola behind him.

- He is the only character that seems to speak (or to whisper) into the ear of the author, to whom he is looking and not to the score ― (1) on his right, behind Paolo’s head ― as is expected from an experienced and professional musician. We think that both circumstances can support our argumentation that he has a role as an expert-instructor. It is notable that while Veronese looks to the score that is behind Titian’s bow (2), and Tintoretto and Bassano look to the opened one on the table (3), the unknown is not reading his own. Titian seems to look to a fourth opened score (4) above the box (behind the hourglass) [56].

- The edition of Ortiz’ second book at Venice eighteen months after the termination of the painting also would be consistent with our interpretation. Therefore, he could perfectly have taken advantage of a trip to the city for commission it and posed as a model [57].

- The canvas contains numerous mannerist artifices described in the literature, however there is one which has not been dealt with so far: the alleged presence of Ortiz in the painting allowed Veronese to obtain a nice symmetry relation between the characters of musicians and painters. The author is portraying himself with the principal exponents of the Venetian Painting School. He blends two groups of five persons (five painters + five musicians), with one person in each group not pertaining to it (Figure 7). We obtain a scheme of the form [4 + 4] + 1 + 1: a total of 6 relevant characters (four painters that are also musicians, one painter who is not a musician and one musician who is not a painter) [58].

- It should be emphasised that the identity of the painters has reliably been accredited (Figure 8) and there is general agreement on those of Veronese, Bassano and Titian. It has been precisely the figure of Ortiz with which authors have struggled. Sixteen of the 34 works we quote here refer to him as Tintoretto (near all the authors later to second Zanetti: so they avoid to mention the violinist and his instrument), while another fifteen do not mention him. Eleven identify Tintoretto correctly as “violinist”, including the original works of Boschini and the first Zanetti. Only five name properly the instruments. Only one makes ascriptions of characters to instruments according to our interpretation (Moriani) ― see Table.

- Related to the horizontal viola da gamba technique, let us point to the fact that nowadays, and from the 17th-century onward, the instrument is played in a vertical position between both legs. We think, however, that two further important factors are decisive in our favour, also in a historical-technical sense of the musical interpretation. Firstly, the technique to play the viola in a horizontal position similar to guitars (vihuelas at this moment), which Diego defended in his treatise [59]; secondly, the ensuing denomination the instrument received in Iberian territories (vihuela española or vihuela de arco) [60].

- The analysis of his presence on the canvas instead of the previously depicted character of another very famous painter, as we will show in the next Paragraph.

Figure 7. The two symmetric groups: Ortiz (left), Veronese, Bassano, Tintoretto, Titian, Benedetto (right). The “missing” Giorgione is on the very left side.

It is then reasonable to suppose that he was in Venice, at least temporarily, the year of canvas completion, sitting as a model to Veronese [61].

Our suggestions are coherent also with his attitude in the scene and with the essential significance of his work in the new polyphonic instrumental improvisation which transformed and propelled the development of the occidental music [62], as well as with the qualified amateur audience (nobles, artists, and humanists) to which his treatise was also addressed [63].

The theory of the second Zanetti (1771) on Tintoretto’s identity had led to many authors to mistakes to our days, as they supposed that the unknown was a famous painter as the rest of performers were, instead of a relevant personage in the “musical environment” which is precisely the central issue displayed in the canvas.

Our main hypothesis arose thanks to the education and inquisitiveness of one of the authors (Alejano), who has identified the matching patterns by repeated contemplation of the painting on the backcloth during many performances as an interpreter.

Figure 8. A. Veronese, B. Jacopo Bassano, C. Tintoretto & D. Titian.

6. Corollary: One maestro on top of the other

The original face covered now by Ortiz seems to be Giorgione’s [64], who is considered to be the most mysterious painter in art history. Like Ortiz, we know very little about his life beyond what Vasari tells us. He never signed his paintings, except two which were signed with his name, but probably by someone else’s hand [65]. The rest of his oeuvre ― painted in a few more than a decade [66] ― is merely being attributed to him. In addition, the literature of the next centuries progressively contributed to his legend mystifying his person, and one has even doubted his very existence for a long time.

In turn, nowadays Giorgione is recognized as the mainstay over which all the Cinquecentto Venetian pictorial art is built [67] as the link between Bellini’s generation and the very Titian, who probably has worked with him in his youth and who finished some of his paintings after his premature death at the age of thirty [68]. It is really difficult, sometimes impossible, to distinguish his portraits from Titian’s early works, a genre which suffered deep transformations by both painters and during the following period [69].

Vasari defined him as the Northern counterpart of Da Vinci, from whom he could have learned his landscape and sfumatto techniques, attuning them in a new and revolutionary way [70]. As Leonardo, he was also a very skillful musician singing and playing lute, and was often employed in contemporary ensembles [71].

Therefore, it is not surprising, given his ancestry in painting with regards to the rest of the group and his own musical competence, that Veronese included Giorgione in the original design perhaps in a role which Ortiz would take over later: as the conductor of the ensemble of violas. This was the first option that the author apparently considered: in this way, Veronese could be showing the “complete” Venetian School in the original version, including both teachers ― Giorgione and Titian ― and their disciples [72].

Our hypothesis, however, is that the presence of Ortiz in Venice in 1563 inspired him to replace Giorgione’s face with that of the maestro from Naples, and in this way to endow the painting with more expressive and symbolic power. It also provided a new artifice which did not weaken the mannerist intention but rather emphasized it. Sure, the good old Giorgione was relegated into oblivion. But in change musicians and painters were merged into the same group also at the level of the Arts, which was his intention already with the painter-musicians from the beginning [73].

Two facts might have facilitated this decision. Firstly, Ortiz was, like Giorgione, a primary figure in his respective discipline. Secondly, Ortiz was still alive ― like all other characters of the ensemble ―, while Giorgione had already died 50 years before. Indeed, he was the most prestigious viola-gambist in Europe at one of the most powerful courts of the moment, Naples.

In the “musical context” of the painting (an ensemble of violas by amateur musician-painters), but also in the social-cultural context of the period, the symbolic power of the musician Ortiz should be considered to be superior to that of the painter Giorgione, even if the latter was very renowned indeed. Figure 9 shows ― between the two known Giorgione portraits ― the approximate character ‘s silhouette which occupied the place of Ortiz in the former design.

As was the case with Ortiz, we think that the general shape and aspect of the face and hair of both portraits show a surprising similarity, which is supported by a similar number of specific features. One could add to the comparison the points 1 and 4 of Section 5 referring to the musician, and some of the scarce biographical data already referred to Giorgione, specially the legend quoted by Colbert in 1671, who included him in the consort already earlier to the former Boschini’s proposal [74].

Figure 9. Giorgione’s self-portraits (inverted) compared to the face under Ortiz’ portrait. A: Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, Germany, ca. 1508. Inv. GG 454. B: X-ray under Ortiz. Louvre Museum Archives (with permission). C: Fine Arts Museum of Budapest, ca. 1508. Inv. Nº 86. D: Giorgione by Vasari (1568, p. 12).

Figure 9. Giorgione’s self-portraits (inverted) compared to the face under Ortiz’ portrait. A: Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, Germany, ca. 1508. Inv. GG 454. B: X-ray under Ortiz. Louvre Museum Archives (with permission). C: Fine Arts Museum of Budapest, ca. 1508. Inv. Nº 86. D: Giorgione by Vasari (1568, p. 12). The facial features which we consider as concurrent are:

- 1) markedly curved profile of the nose;

- 2) size and proportion of the nose;

- 3) little mouth with thin lips;

- 4) left descending corner of the mouth;

- 5) probable position (due to the different angle) [75], shape and size of the eyebrows;

- 6) similar marked eye sockets;

- 7) wrinkle that descends from the left lagrimal;

- 8) shape of the chin;

- 9) receding hairline with a right angle over the temple;

- 10) global contour of the face;

- 11) global contour of the hair;

- 12) global aspect of the head.

So, we conjecture:

- (1) that the second ring on the right thumb of Titian could be representing his dead (and omitted) colleague [76]; and

- (2) that the 17th-century legend on Giorgione’s presence can only proceed from those who saw the canvas while it was painted. As Colbert mentions it just after seeing the picture in its original place, it is probable that he was informed there on the subject [77].

Figure 10. Giorgione ‘s approximate silhouette holding lute in the original design.

7b. Quotations [are located inside the notes]

[1] Seignelay (1865, p. 461) : “Il y a dans le réfectoire un très-beau tableau de Paul Veronese; il représente les noces de Cana, et comme c’est un fort gran tableau dans lequel il y a un grand nombre de personnages, ce peintre y a mis les portraits des quatre illustres peintres de son temps, dont il en est un luy-mesme. Les autres sont le Giorgione, le Tintoret et le vieux Bassan” (sic.).[2] Boschini (1674, Breve Instruzione): “Il Vecchio, che suona il Basso, é Tiziano; l’altro che suona il Flauto, é Giacomo da Bassano; quello che suona il Violino, é il Tintoretto, ed il quarto vestito di bianco, che suona la Viola, é lo stesso Paolo” (sic.).[3] Wright (1720) : “… Paolo’s Wife is painted for the Bride: himself, Titian, and one of the Bassans, are joining in a Concert of Musick, and Paolo’s Brother is Governour of the Feast, and is tasting the Wine” (sic.).[4] Zanetti (1733, p. 473): “Di rimarcabile evvi oltre la moltiplicità di figure, un concerto di suonatori, il primo de’ quali, che suona la viola è il ritratto dello stesso Paolo, il secondo col violone è Tiziano, il terzo col violino il Tintoretto, e quello finalmente col flauto è il Bassano vecchio” (sic.).[5] de Brosses (1739): “… le Titien joue de la basse; Paul joue de la viole; le Tintoret du violon, e le Bassan de la flûte …” (sic.).[6] Northall (1766): “… the musicians are the portraits of the famous masters of the Venetian school: Paul himself, Titian, Tintoret, Bassan Vecchio, and Palma Vecchio, his brother, is represented in the governor of the feast” (sic.).[7] Richard (1766): “Le peintre a placé dans une galerie une troupe de mousiciens, où il s’est peint lui-même jouant de la viole, le Titien du violoncel, le Tintoret du violon, & Léandre Bassan de la flûte” (sic.).[8] Cochin (1769): “Celui qui joue de la viole est P. Veronese lui-même; celui qui joue du violoncelle est le Tiziano; le troisième, qui joue du violon, le Tintoretto; enfin celui qui joue de la flûte est le Bassano, surnommé le vieux” (sic.).[9] Miller (1770): “I was not permitted by the monks to enter their refectory, as no women are suffered to penetrate so far: I therefore waited for M—in the church; he made a note of it: he thinks it a very fine picture, and believes there are more portraits amongst the personages, than the monks apprehend: amongst the musicians they point out those of Tiziano, Tintoretto and Bassano; he thinks the coloring, ordonnance, grouping & c. in Veronese’s best manner” (sic.).[10] Burney (1771): “… he portrays himself playing a six-string viol, Titian with a violone, an old man, Tintoretto with a four-string violin and short bow, a young man, and Bassano with the flute” (sic.).[11] Zanetti (1771, pp. 170-1): “Tiziano è il suonatore di contrabbasso. Paolo ritrasse sè stesso nella figura che suona il violoncello, in abito giallo; (...). Nell’altro suonatore ch’è accanto a esso Paolo parimente con un violoncello o altro simile istrumento; e che mostra di suonare a concerto; si crede con ragione che sia dipinto Jacopo Tintoretto” (sic.).[12] Lavallée & Caraffe (1813): “Il s’est représenté lui-même, vêtu de blanc et jouant du violoncelle. Le Tintoret derrière lui, et le Titien en face jouant de la basse. Selon Boschini, celui qui joue de la flûte est le Bassan dit le vieux, mais alors dans son jeune âge” (sic.).[13] Zannandreis (1836): “Nella banda de’ suonatori vi si scorge lo stesso Paolo, Tiziano, il Bassano ed il Tintoretto; e pretendesi aver lui ciò adoperato per dinotare che in fatto di professioni erano essi tutti d’accordo, come avviene nella musica, quantunque suoni ognuno una parte diversa” (sic.).[14] Sauzay (1884, p. 11): “Paul Véronèse et le Tintoret jouent de la viola da braccia, et le Titien de le contre-basse de viola ou violone. En outre de ces violes on trouve aussi dans ce même tableau une flûte, une trompette et un violon (sic)”.[15] Rolland (1908, p. 46): “… Titien tenant la contrabasse, Véronèse et Tintoret jouant du violoncelle et Bassano de la flûte” (sic).[16] Bell (1904, p. xii): “More remarkable and more interesting than any of these figures are, however, the excellent Portraits of the artist himself, Tintoretto, Titian, and Giacomo da Ponte [Bassano], who are introduced as musicians at a round table in the foreground, …” (sic.).[17] Castre (1912, p. 44): “The octogenarian bending over his viol, is a portrait of Titian; Bassano is playing the flute; Tintoretto and Veronese himself draw their bow across the strings of a ‘cello” (sic.).[18] Cocke (1980, p. 64): “Boschini is wrong in identifying the violinist as Tintoretto who is more likely to be shown playing the second viol next to Veronese; the bearded and foreshortened head fits in with the self-portraits of Tintoretto in the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Louvre … It is not possible to check that Jacopo Bassano plays the cornetto muto” (sic.).[19] Pignatti (1989, p. 12): “… among them Veronese himself playing the viola da braccio in a concert whose other members can be identified as Titian with a viola da gamba, Tintoretto with a viol, and perhaps also Bassano” (sic.).[20] Rearick (1989, p. 118): “Among these, the only one that carries conviction is the viola da braccio player in the Marriage Feast at Cana, identified in 1771 by Zanetti as Paolo's self-portrait in the company of Titian, Tintoretto, and Jacopo Bassano” (sic.).[21] Bosseur (1991): “Au centre le peintre s’ est représenté lui-même jouant de la viole de bras, tandis que Titien joue de la contrabasse, bassano de la flûte et le Tintoret de la viole” (sic.).[22] Bassano (1994, p. 11): “… there is a group of five musicians playing two tenor viols, a violin, a cornett, and a violones” (sic.).[23] Brown (2000, p. 64): “Veronese seated with a viola da braccia; Tintoretto (also with a viola da braccia), whispering to Veronese from behind; Jacopo Bassano playing a flute; and Titian with a viola da gamba. The fifth placer with a violin cannot be identified” (sic.).[24] Buisine (2000, p. 99): “… les musiciens parmi lesquels un joueur de sacquebouche, deux joueurs de viole de gambe, un joueur de cornett droit, un joueur de violon, un joueur de contrabsse de viole … (sic.)”.[25] Cocke (2001, p. 173): “… the musicians represented Veronese in a resplendent white brocade, with Tintoretto, foreshortened, both playing the tenor viol, opposite the aged Titian in ‘Titian red’, bowing away at his bass-viol” (sic.).[26] Bertelli (2002, p. 23): “According to Marco Boschini, the quartet in the foreground is made up of Titian, Jacopo Bassano, Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese. This is a tradition dating back to the Florentine Quattrocento portraits of major contemporary artists” (sic.).[27] Hagen & Hagen (2003, p. 157): “Si esto fuera verdad, cosa factible comparando retratos, los indiscutibles maestros de la pintura veneciana del siglo XVI, los tres grandes coloristas, se habrían reunido aquí para hacer música” (sic.).[28] Viallon (2004, Nota 11): “La composition de l’ orchestre: deux joueurs de viole de gambe dont le premier, tout de blanc vêtu, serait un autoportrait de Véronèse et l’ autre serait un portrait de Jacopo Tintoret, un joueur de cornet droit, un joueur de sacquebute, un joueur de rebec ou violon et un joueur de basse de viole en manteau rouge qui serait le portrait du Titien” (sic.).[29] Di Monte (2007, p. 160): “Se, infatti, non sarebbe poi così arduo riconoscere il vecchio Tiziano nell’anziano vestito di rosso, a destra, il confronto tra i ritratti noti di Tintoretto e la sua presunta effige nel suonatore di viola in secondo piano (l’unico candidato possibile, peraltro) non pare molto stringente ... che nessuno degli esecutori presenti può ritrarre Jacopo Bassano” (sic.)[30] Zirpolo (2008, p. 266): “In front of the table are musicians who entertain the guests. These are portraits (from left to right) of the artist Jacopo Bassano, Veronese himself, and Titian. With their inclusion, Veronese made his case for painting as a liberal art comparable to music” (sic.).[31] Bätschmann (2008, pp. 185-6): “Titian with a viola da gamba, Tintoretto and Veronese with viols, Veronese’s brother with a lira da braccio and perhaps Jacopo Bassano with a flute”. (sic.)[32] Hanson (2010, p. 47): “Continuing upward, the four musicians have been identified as Veronese in white, with Tintoretto (both playing the viola da braccio), Jacopo Bassano (playing the flute), and Titian in red (playing the viola da gamba)” (sic.).[33] Dardel (2012): “… Tiziano aparece vestido de rojo tocando la viola da gamba, a su lado Tintoretto toca, junto al propio Veronés – quien se autorretrató de blanco al lado izquierdo – la viola da braccio y a su lado, Jacopo Bassano en la flauta” (sic.).[34] Moriani (2014, p. 84): “Quattro di loro sono stati così identificati: Veronese in bianco (con la viola da gamba), Tintoretto (col violino), Jacopo Bassano (col cornetto) e Tiziano in rosso (con il contrabbasso). L’autoritratto di Veronese occupa una posizione particolarmente evidente nella composizione, situato in asse con Maria. Seminascosti, dietro di lui, ci sono altri due musici: uno con la viola da gamba e l’ altro col trombone” (sic.)

TABLE. Adscription of characters to instruments by author (see Note 18). Names in blue colour point to correct adscriptions. Let us emphasize that “contrabass” is not an appropriate word for Titian’s instrument as it is a modern one. Nevertheless, it is included here as correct, as are those instrument names which are suitable (Zanetti, Sauzay and Bassano: violone; Viallon: basse de viole). However, that of Paolo (viola) is not remarked when the gamba type is not mentioned. Ditto, we have listed as correct “violin”, “violon” or “viola” for Tintoretto’s instrument, as they identify correctly the musician’s character (question marks mean that there is no reference to this viola soprano or its player). See Lafarga & Sanz eds. (2018, in press).

Prefacio

El lienzo de Paolo Caliari el Veronés Las Bodas de Caná, comenzado en junio de 1562 y entregado en octubre de 1563 a sus propietarios los monjes benedictinos del monasterio de San Giorgio Maggiore de Venecia, fue en origen y casi hasta su finalización un homenaje póstumo al maestro fallecido 50 años antes, y considerado el fundador de la así llamada “escuela veneciana de pintura” Giorgio de Castelfranco, apodado Giorgione.

El diseño y la composición del consort que ocupa la escena central del cuadro sufrió un cierto número de importantes reestructuraciones sucesivas hasta configurar el ensemble actual que se observa en el lienzo acabado, en el cual un nuevo personaje muy relevante en la escena musical internacional del momento ocupó el lugar del maestro veneciano ausente.

Muy probablemente, el famoso violagambista de origen español Diego Ortiz, maestro de capilla en activo de la Corte de Nápoles hasta su muerte en 1570, visitó la ciudad durante los últimos meses de la elaboración de la obra, acaso con motivo de la futura edición de su segundo libro en Venecia a cargo del editor Antonio Gardano, libro que fue en efecto publicado poco más de un año después de la finalización del cuadro, en 1565.

Nuestra conjetura es que durante su estancia en la ciudad posó como modelo para el Veronese, sustituyendo definitivamente a Giorgione y transformando finalmente el ensemble instrumental en un consort de violas da gamba. Sin embargo, su aparición en la obra definitiva tan sólo representa la última de las transformaciones a las que Paolo Caliari sometió a su propia obra, estando motivadas todas las anteriores por razones ajenas a la indiscutible relevancia del maestro napolitano en el entorno musical internacional del momento.

La identificación del personaje que parece susurrar al oído del Veronés, con un instrumento muy similar al del propio autor, ha acarreado numerosas interpretaciones erróneas en la literatura desde que Antonio Zanetti el Joven (1754-1812) modificó la tradición erudita en 1771 hasta nuestros días, al afirmar que “si crede con ragione che sia dipinto Jacopo Tintoretto” (sic.) .

Hasta este momento, ningún otro autor se había referido al desconocido que acabaría ocupando el lugar de Giorgione, y aquellos que se refirieron a la identidad de los pintores-músicos habían seguido la tradición iniciada por Boschini en 1674, que identificaba a Tintoretto en el violinista y no en nuestro barbudo napolitano.

Desde la nueva propuesta no comprobada del segundo Zanetti (hijo), los autores que han querido mencionar a nuestros protagonistas se dividen en dos grupos: aquellos que siguiéndole identifican al violagambista con Tintoretto omitiendo mencionar al violinista, y aquellos que eluden referirse al desconocido tras Veronese. Un tercer grupo más impreciso se refiere tan solo a algunos personajes sin mencionar a los demás, tanto en lo relativo a los pintores-músicos como a los instrumentos.

La nuestra es la primera interpretación razonada en la literatura sobre la identidad de todos los músicos que aparecen en la escena.

Es acorde, además, con la muy reciente de Moriani, quien al cabo ha identificado correctamente todos los instrumentos junto con sus respectivos intérpretes, aludiendo igualmente a nuestro protagonista como desconocido, del cual tan solo dice que “Seminascosti, dietro di lui, ci sono altri due musici: uno con la viola da gamba e l’ altro col trombone” (sic.) .

La interpretación original de Boschini ha sido calificada como una “leyenda” más entre otras a las que la fama inmediata del cuadro habría dado lugar hasta nuestros días.

Sin embargo, sorprendentemente la leyenda que circulaba en el propio monasterio un siglo después de su finalización decía que en él figuraban, además del autor, “… Giorgione, Tintoretto, y el viejo Bassano” (sic.) . Jean-Baptiste Colbert, ministro de Luis XIV de Francia, había visitado la isla en 1641, y la dejó consignada de vuelta a su país tres meses despúes, al escribir la relación de sus viajes por la Italia contemporánea. La leyenda sin duda provenía de las propias autoridades del monasterio, y sólo podía proceder en última instancia de aquellos que habían contemplado el cuadro antes de su finalización un siglo atrás.

La importancia de Giorgione en la Venecia de 1500 está fuera de toda duda, toda vez que fue compañero, si no maestro, del mismo Tiziano en su juventud, en los talleres de Giovanni Bellini y después en algunos de los trabajos que Giorgione llevó a cabo en la ciudad durante su breve actividad pictórica, concentrada en poco más de una década a comienzos del siglo XVI.

Giorgione había dirigido en 1508 los trabajos de restauración de las fachadas de la Fondaco dei Tedeschi, la asociación de empresarios alemanes de la ciudad y uno de los mayores y más emblemáticos edicificios de Venecia, gozando de total libertad en la elección de temas y figuraciones, si bien la empresa no finalizó a entero gusto del pintor, quien acabó transfiriendo la finalización de la misma a un consorcio de expertos entre los que figuraba el mismo Bellini.

Giorgione fue un modelo reconocido, admirado, “imitado” y venerado por generaciones enteras de pintores en Italia durante todo el Cinquecento, y se le considera el primer innovador en muchas de las técnicas y características que definieron en adelante a los pintores venecianos del Renacimiento, además de en determinados géneros como el retrato, el desnudo femenino, el tratamiento del paisaje y también la pintura de formato reducido para coleccionistas privados.

1. El “Demonio Etrusco” del Manierismo y el Círculo de Oro

Seguidor de la doctrina manierista del diseño como base irrenunciable para un pintura elegante, refinada e intelectual , la obra primera de Veronese hasta 1555 se conoce como la del “demonio etrusco del manierismo” . Fue esta una corriente estética que en pintura tuvo uno de sus focos pictóricos principales en Venecia, y en la que Giorgione , Tiziano (su maestro), él mismo y también nuestros protagonistas, tuvieron un papel decisivo.

Figura 2. El consort de músicos (4 pintores y Ortiz). Louvre, Inv. 142.

Una de las técnicas del nuevo estilo consistía en sustituir o codificar elementos en las obras mediante la inclusión de personajes o símbolos coetáneos o consagrados por la tradición, una práctica que fue rechazada por la Inquisición pero que gozó de gran auge entre los humanistas protestantes y en aquellas cortes o repúblicas en las que aquella no tuvo plena jurisdicción ― p.e. en Venecia.

El propio Veronese utilizó el manierismo como recurso para acercar la pintura al concepto de arte liberal, rango del que ya gozaba la música : la técnica le permitía escapar del criterio mecánico (imitativo) atribuido hasta entonces a la reproducción pictórica como un mero reflejo de la realidad. Esta fue probablemente una de las causas principales que defendió en Las Bodas de Caná, mezclando dos grupos de artistas, músicos y pintores.

Las numerosas “cenas” y situaciones similares pintadas por Veronese y sus colegas venecianos representaban determinados relatos bíblicos como auténticas celebraciones en la rica ciudad de su tiempo, y en este lienzo, el autor incluyó su propio autorretrato y los de sus compañeros, los pintores contemporáneos más destacados de la Escuela Veneciana, identificando a todos ellos con un anillo de oro en el dedo meñique.

2. Un encargo valioso con gente importante

La obra fue el encargo de los monjes benedictinos de la Basílica de San Giorgio Maggiore de Venecia, emplazada en una pequeña isla junto a la Plaza de San Marcos. El lienzo debía adornar una pared de la sala recientemente reconstruida por Palladio , quien le consiguió el encargo, y ocupaba 66 m2, un lienzo de dimensiones considerables (994 cm x 677 cm). El trabajo le ocupó 15 meses ayudado por su hermano.

La escena muestra el primer milagro de Jesús al convertir el agua en vino en una boda galilea, y ninguno de los personajes representados aparece hablando o conversando, dado que una de las reglas del monasterio era la del silencio en el refectorio, durante las comidas .

El convento era visitado frecuentemente por artistas y huéspedes importantes, y el refectorio estaba incluido en los libros de viajes y guías de Venecia de la época, de modo que con el trabajo se quiso significar también el poder y la riqueza del monasterio, uno de los más importantes del momento . Muchos de los personajes que aparecen en el lienzo pertenecen a la alta sociedad y algunos de ellos con relevancia internacional, incluyendo reyes y monarcas.

Figura 3. Ortiz y el Círculo de Oro completo (5 pintores incluyendo a Benedetto Caliari, hermano del Veronés, a la derecha en pie).

El contrato especificaba determinadas exigencias, como la inclusión del mayor número de figuras posible o el uso de colores y pigmentos de alta calidad, con minerales preciosos en su composición. Durante la década siguiente, los talleres de los 4 pintores representados produjeron numerosas obras similares en los refectorios de los monasterios venecianos .

El lienzo se hizo tan famoso que muchos acudían a la ciudad para contemplarlo. Príncipes y gobernantes europeos solicitaron copias repetidamente, y muchos pintores y escultores acudían a San Giorgio tan solo para pedir el permiso de los monjes para reproducir la obra. La situación llegó a tal extremo que, en el Capítulo del 17 de diciembre de 1705, estos decidieron no conceder ninguno más.

3. Un cuarteto de cuerda y un instructor de viola da gamba

La figura de Jesucristo, un tema habitual en la época, aparece como era la costumbre en el centro geométrico del diseño , pero como figura secundaria tras el grupo de músicos, mientras que los supuestos protagonistas del evento, los novios, aparecen sentados en el extremo izquierdo del cuadro desde el observador. El cuerpo central lo compone un consort de 4 violas da gamba: el propio autor (V) y un personaje desconocido tras él, ambos aparentemente con violas tenor, y otros 2 pintores famosos, Tintoretto (Tt) al “violín” y Tiziano (Tz) a la viola bajo. Entre Tintoretto y el personaje desconocido aparece otro famoso pintor, Bassano (B), tañendo un instrumento referido habitualmente como una flauta, pero que en realidad es un cornetto casi sin curvatura, lo cual puede apreciarse con claridad en la boquilla sobre sus labios . El hermano del autor es la figura en pie detrás de Tiziano. Incluyendo el estudio reciente de Moriani (véase más abajo), al menos treinta trabajos sin duda prestigiosos en el campo de la pintura o de la biografía (véase la Tabla), han aludido a la identidad de los músicos del cuadro, pero muchos contienen errores y de ninguno se desprende quién pueda ser el desconocido, aún cuando algunos se refieren a él acaso como Tintoretto, aludiendo a un cierto parecido (a nuestro entender erróneamente, como mostramos igualmente en la Figura 8C).

Figura 4. El Círculo de Oro (5 pintores), y el quinteto (consort) con Ortiz.

El dibujo no muestra los anillos de Tiziano (anular izquierdo y pulgar derecho) ni el meñique de Benedetto, en pie, fuera de la silueta).

Figura 5. Las Bodas de Caná. Detalle del consort de violas y el cornettista (Bassano).

La identificación de los personajes que ocupan el centro de la escena (cuatro pintores y un desconocido) se basa en el trabajo de Marco Boschini, quien identificó al cuarteto de pintores-músicos (no de violistas; aquí se incluye a Bassano) como el “Círculo de Oro”, a partir de los anillos que lucen en el dedo meñique (aquí se incluye a Benedetto) .

Sin embargo ― y este es un punto crítico para nosotros ―, no menciona al músico desconocido detrás de Veronese, quien, además, tampoco luce anillo.

Se podría argumentar que la posición de su mano sobre el mástil no permite apreciarlo, pero nosotros conjeturamos en cambio que el autor tuvo la oportunidad de mostrarlo si hubiese sido su deseo ― como así lo hizo en el caso de su hermano, en pie a la derecha, que sí era pintor (Figuras 4-5). En el lienzo se aprecia que en su meñique izquierdo hubiera sido perfectamente visible.

Dos siglos después, Zanetti el Joven (1771) propuso una nueva teoría no probada que postula a nuestro protagonista como Tintoretto aunque sólo cita tres músicos omitiendo al violín y al cornetto: dice que en el personaje junto a Paolo “se cree reconocer con fundamento a Jacopo Tintoretto” (sic.) .

Sin embargo, hasta entonces, 5 de los 9 autores que habían aludido a los músicos identificaban a Tintoretto como el violinista (los otros 4 no mencionan instrumentos) y ninguno mencionaba al desconocido .

Un estudio reciente de Ton (2012) cuestiona la propuesta de Boschini de 1674 como “infundada” (sic., p. 32) y sugiere que la suya no era una idea original sino fruto de una suerte de leyenda que acompañaba al cuadro desde tiempo atrás aumentando su aura.

Como prueba de ello, aduce que ya había sido consignada tres años antes por Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Sorprendentemente, Colbert dice tras visitar el refectorio de San Giorgio en 1671 que a Paolo le acompañan “… Giorgione, Tintoretto, y el viejo Bassano” (sic.) .

La nueva propuesta de Zanetti fue después retomada por Sauzay , Rolland y otros con los mismos errores reiterados con frecuencia en la literatura posterior . Muchos se han referido sólo a cuatro músicos ― incluyendo a Veronese ― omitiendo a menudo la figura del “violinista” .

Pignatti, p.e., enumera correctamente algunos músicos e instrumentos de derecha a izquierda, (incluyendo a Tintoretto: “viola”), aunque no menciona al desconocido y confunde el instrumento de Paolo, al que nombra “viola da braccio” . Rearick cita la opinión de Zanetti y parece nombrarlos de derecha a izquierda sin alusión a los diseños respectivos, pero repitiendo la confusión con el instrumento de Veronese . El compositor Bosseur, como Pignatti, asignó con propiedad los instrumentos a sus respectivos personajes, aunque sigue llamando “flauta” al cornetto y “viola da braccia” a la viola tenor, sin mencionar al desconocido .

Hanson describe igualmente cuatro músicos: Tiziano a la “viola da gamba” y el cornettista, del que dice tocar una “flauta” (sic.), mientras que en sintonía con Zanetti y Cocke dice que ambos Veronese y Tintoretto tocan viola da braccio . Esta apreciación, sin embargo, es técnicamente incorrecta, pues tan sólo el segundo (el violinista) la toca, mientras que Veronese tañe un instrumento casi idéntico al del desconocido ― una viola da gamba, un término técnico que usa en cambio con propiedad para Tiziano .

Dardel identifica a los mismos personajes del mismo modo . Dos matices y precisiones que cabe añadir aquí son: 1) que los instrumentos de Veronese y el desconocido son una viola tenor y un bajo melódico respectivamente, mientras que el de Tiziano es una viola contrabajo ; y 2) que este modo de tocar ― sostener la viola tenor en posición horizontal en vez de entre las piernas como se hace hoy y el calificativo gamba indica ― era la técnica “vihuelística” que precisamente defendía Diego Ortiz (1553) .

Otros trabajos han insistido en los mismos asertos, remarcando que el violinista no ha podido ser identificado . Bertelli nombra tan solo cuatro músicos de derecha a izquierda, omitiendo al violinista y atribuyendo de nuevo la identidad de Tintoretto al desconocido “según la tradición de Boschini” (sic.) ― quien, por el contrario, había sido el primero en atribuir con acierto este personaje al violinista .

Otros han retomado la propuesta del segundo Zanetti afirmando que Tintoretto se parece más a nuestro músico desconocido al compararlo con dos de sus autorretratos (Figura 8C) .

Esta es una opinión que evidentemente no podemos compartir. Viallon, p.e., también nombra correctamente los instrumentos pero insiste en que el desconocido es Tintoretto .

Bassano es el primero en nombrarlos todos correctamente, aunque él mismo no se pronuncia sobre la identidad de Tintoretto ni del desconocido , mientras que Buisine parece ser el segundo, aún cuando elude igualmente identificar a los músicos .

Zirpolo menciona tan sólo tres músicos, sin orden y sin referirse a Tintoretto ni al desconocido: “… hay retratos (de izquierda a derecha) del artista Jacopo Bassano, el propio Veronese, y Tiziano” (sic.) . Bätschmann incluso llega a identificar al violinista como Benedetto Caliari .

Por último, un monográfico reciente dedicado a las cenas que pintó Veronese enumera todos los músicos y sus instrumentos, en el mismo sentido que hemos defendido aquí según la propuesta original de Boschini y mencionando por fin al desconocido sin identificarlo .

Muchos artistas e intelectuales renacentistas se interesaron y fueron diestros en otras disciplinas además de la propia, sobre todo en música y especialmente en Venecia .

Tiziano había recibido un órgano en pago por un retrato del luthier y constructor Alessandro Trasuntino , y Tintoretto era probablemente un músico competente ya desde su juventud . El mismo Veronese fue un entusiasta músico amateur: en 1558 había diseñado el complejo exterior del órgano de la iglesia de San Sebastiano, y a finales de año también los planos para otro nuevo en la iglesia de San Geminiano, en la Plaza de San Marcos . Giorgione era un hábil cantante y diestro en el laúd, como fue el caso de muchos humanistas .

Permítasenos ahora enfocar al desconocido cuyo rostro está junto al del propio autor, asumiendo de este modo un papel muy relevante. En el diseño original, iluminado mediante rayos-X, sus rasgos no estaban presentes , lo cual da pie a sostener que fue añadido a posteriori (antes de ser acabado) debido al prestigio de Ortiz con las violas y a su probable papel de instructor de personajes importantes contemporáneos .

Este personaje mira a Paolo y no a su propia partitura como sí hace el resto de músicos , además de exhibir un gesto claro de indicación verbal junto a su oído que parecería romper la regla de silencio de los benedictinos.

Resultaría incoherente, dada su actitud, asumir que pudiera ser un músico anónimo, como tampoco lo son los pintores-músicos a los que acompaña. Sin embargo, la ausencia de anillo y la suya propia del diseño original le excluyen explícitamente del grupo de pintores. De modo que lo más probable es que se trate de un músico de oficio (profesional), alguien relevante en su característica distintiva dentro del quinteto: la de ser un violagambista importante.

Ya hemos apuntado cómo el camino estético emprendido por el propio Veronese ― equiparar el arte de la Pintura al resto de artes liberales ― había sido ya alcanzado por los músicos, a quienes en esencia representaría la figura emblemática de Diego Ortiz frente a los músicos-pintores-amateurs.

4. Un parecido sorprendente: doce rasgos faciales coincidentes

El hecho conocido de que en ocasiones los impresores usaban un mismo diseño para ilustrar portadas de diferentes libros, no obsta para que el dibujo del tratado de Ortiz (1553) sea él mismo, puesto que no se conocen otras ediciones de otros autores con el mismo patrón. La autenticidad del grabado está refrendada por el prestigio de los editores, tipógrafos igualmente de la Accademia Romana .

Los hermanos Dorico se especializaron en la impresión de obras musicales de autores renombrados desde 1539 a 1555, circunstancia que permite conceder crédito a sus representaciones en grabados de las facciones de autores importantes. Este es el único retrato conocido de uno de los violagambistas europeos más relevantes en el momento de su publicación.

Sus rasgos son bastante inusuales: aunque puedan estar presentes en muchos otros personajes individualmente o combinados, es improbable que aparezcan reunidos a la vez en dos violagambistas famosos diferentes distantes 10 años en el tiempo. Y del mismo modo, que otros músicos especialistas coetáneos pudiesen coincidir en tantos de ellos.

Figura 6. Detalle del violagambista desconocido comparado con el retrato de Ortiz en su propio tratado.

Creemos que la forma y aspecto generales de rostro y cabello guardan sorprendentes similitudes en ambos retratos. En nuestra opinión, existen al menos 12 elementos gráficos coincidentes entre ambos diseños:

- forma global del peinado;

- tipo de cabello: ondulado y semi-ensortijado;

- forma y densidad de la barba;

- pico de cabello que se prolonga en la frente;

- contorno del pelo y una arruga que se pronuncian en la sien;

- tres arrugas longitudinales de la frente y el pico central descendente;

- tres arrugas en la comisura del ojo que parecen prolongarse bajo la sien;

- bolsa longilínea bajo el ojo;

- forma, contorno y tamaño de la nariz;

- forma de las alas y arrugas de la base de la nariz;

- forma y tamaño relativo de la oreja;

- proporción de los rasgos faciales y aspecto global del rostro.

Por lo demás, el “violinista” (Tintoretto, Figura 8C), que parece bastante más joven que el desconocido, tenía 44 años a la entrega del lienzo, mientras que Diego tenía 53, edades que casan mejor ― respectivamente y también entre ambos ― con los rasgos que proponemos aquí.

5. Conclusiones: siete argumentos encadenados

Otras consideraciones argumentales, además de los anillos que identifican a los pintores y el parecido ya citado, sostienen nuestra hipótesis principal:

- La relevancia de Ortiz como músico contemporáneo fue enorme: era una de las figuras más representativas del arte de la interpretación con violas da gamba y Maestro de la Capilla Real de Nápoles, uno de los conjuntos más importantes del Renacimiento europeo, durante más de una década . Está por tanto justificado suponer que Veronese decidiese incluir al maestro en el cuadro tañendo la viola tenor detrás de sí mismo.

- Es el único personaje en la escena que parece hablar (o susurrar) al oído del autor, a quien mira y no a su partitura ― (1) a su derecha, tras la cabeza de Paolo ― como se esperaría de un músico experto y profesional. Creemos que estas dos circunstancias pueden apoyar nuestra argumentación relativa a su papel como instructor. Resulta notable que mientras Veronese mira a la partitura que se halla detrás del arco de Tiziano (2), y Tintoretto y Bassano miran a la que está abierta sobre la mesa (3), el desconocido no lee la suya. Tiziano parece mirar a una cuarta partitura abierta (4) sobre la caja en la mesa (tras el reloj de arena).

- La publicación del segundo libro de Oritz en Venecia 18 meses después de la finalización del cuadro también es consistente con nuestra interpretación, de modo que podría perfectamente haber aprovechado su viaje previo a la ciudad para encargar la edición de su nueva obra y haber posado como modelo .

- El lienzo contiene numerosos artificios manieristas ya descritos en la literatura, pero uno que no ha sido observado hasta ahora consiste en la posibilidad de que la supuesta presencia de Ortiz en el cuadro permitiese a Veronese obtener una bella relación de simetría entre músicos y pintores. El autor se retrata a sí mismo con los principales exponentes de la Escuela Veneciana de pintura, mezclando dos grupos de 5 personas (5 pintores + 5 músicos), con una persona de cada grupo que no pertenece a la vez a ambos (Figura 7). De este modo se obtiene un esquema de la forma [4 + 4] + 1 + 1: un total de 6 personajes relevantes (4 pintores que son también músicos, un pintor que no es músico y un músico que no es pintor) .

- Hemos de enfatizar aquí que la identidad de los pintores está acreditada con fiabilidad (Figura 8) y en general hay pocas dudas sobre Veronese, Bassano y Tiziano: ha sido precisamente la figura de Ortiz la que casi todos los autores han omitido o entrado en conflicto con ella. Dieciséis de los 34 trabajos considerados aquí se refieren a él como Tintoretto (casi toda la tradición posterior al segundo Zanetti: eluden así además referirse al violinista y a su instrumento), mientras que otros quince ni siquiera lo mencionan. Once identifican correctamente a Tintoretto como “violinista”, incluyendo los trabajos originales de Boschini y el primer Zanetti. Solo cinco nombran con propiedad los instrumentos. Solo uno adscribe los personajes a sus instrumentos como proponemos aquí (Moriani) ― véase la Tabla.

- En relación con la técnica horizontal para la viola da gamba, permítasenos apuntar el hecho de que en nuestros días, y ya desde el siglo XVII en adelante y como su nombre indica, el instrumento se toca en posición vertical entre ambas piernas. Sin embargo, creemos que existen dos argumentos más muy importantes a nuestro favor, también en un sentido histórico-técnico y estético de la interpretación musical. El primero la técnica de tocar la viola tenor en posición horizontal que aparece en el cuadro ― similar a la de las guitarras (vihuelas en este momento) y precisamente la defendida por Diego en su tratado ― y el segundo la denominación que recibía en estos tiempos el instrumento en los territorios de la Península Ibérica (vihuela española o vihuela de arco) .

- El análisis de su presencia en el cuadro sustituyendo la faz de un no menos famoso pintor, tal y como se ilustra en el Apartado siguiente.

Figura 7. Los dos grupos simétricos y el omitido Giorgione (fuera del cuadro): Ortiz (izquierda), Veronese, Bassano, Tintoreto, Tiziano, Benedetto (derecha).

En resumen, un buen número de evidencias relevantes apoyan nuestra hipótesis de que el personaje desconocido es Diego Ortiz: el momento histórico, su relevancia en el instrumento al que dedicó su tratado, las circunstancias intelectuales y geográficas apuntadas (la técnica horizontal y la edición del segundo libro en Venecia), y ― de forma importante ― la sorprendente similitud de los rasgos faciales en el cuadro y en el grabado de su propio tratado, así como las consideraciones estéticas relativas a la simetría.

Es por tanto razonable suponer que estuvo en Venecia, al menos temporalmente, el año de la finalización del lienzo, posando como modelo para Veronese.

Figura 8. A. El Veronés, B. Jacopo Bassano, C. Tintoretto y D. Tiziano.

Nuestras propuestas son coherentes igualmente con la actitud de Ortiz en la escena y con la importancia crítica de su obra en la nueva improvisación polifónica instrumental que transformó e impulsó el desarrollo de la música occidental en adelante , así como con la audiencia amateur cualificada de nobles, artistas, y humanistas, a los cuales también se dirigía su tratado .

La teoría del segundo Zanetti (1771) sobre la identidad de Tintoretto ha llevado a muchos autores a confusión hasta nuestros días, al suponer que el músico “añadido” era igualmente un pintor de renombre como los demás componentes del consort, en lugar de un personaje relevante en el “ambiente musical” que es precisamente el tema central del cuadro.

Nuestra tesis principal tiene su origen en la formación y la curiosidad académica de uno de los autores (Alejano, él mismo violista), quien acabó identificando ambos patrones faciales coincidentes tras la repetida contemplación del cuadro como telón de fondo escénico durante muchas representaciones como intérprete.

6. Corolario: dos maestros superpuestos

El rostro original que se halla bajo la faz de Ortiz parece corresponder a Giorgione , quien ha sido repetidamente considerado el pintor más misterioso de la Historia del Arte.

Como en el caso de Diego, existen escasos datos sobre su vida, más allá de lo que nos cuenta Vasari, y tampoco firmaba sus cuadros: salvo dos que probablemente firmó por él otra mano distinta , todo el resto de su obra ― concentrada en poco más de una década ― le es atribuida. Más aún, la literatura de los siglos posteriores contribuyó a su leyenda mitificando progresivamente su figura y durante mucho tiempo incluso se llegó a dudar de su misma existencia.

Hoy día en cambio es reconocido como el pilar sobre el que asienta todo el arte pictórico veneciano del Cinquecentto . Se le considera el nexo entre la generación de Bellini y el propio Tiziano, quien probablemente trabajó con él en su juventud y completó algunos de sus cuadros tras su prematura muerte a los 30 años : resulta muy difícil y en ocasiones imposible diferenciar sus retratos, un género que fue profundamente transformado también por ambos pintores .

Vasari le definió como la contrapartida nórdica de Da Vinci, de quien pudo haber aprendido sus técnicas paisajísticas y sfumatti y haberlas desarrollado de un modo novedoso y revolucionario . Como Leonardo, también era diestro cantando y tañendo laúd, y a menudo era contratado para tocar en eventos musicales .

No resulta por tanto sorprendente, dados su ascendiente pictórico sobre el resto del grupo y su propia competencia musical, que fuera incluido en el diseño original quizá en el mismo papel que más tarde recabaría Diego: la conducción del consort de violas.

Esta parece ser la primera opción que el autor consideró, de modo que en origen podría estar mostrando en efecto a la Escuela Veneciana de su tiempo “al completo”, ambos maestros ― Giorgione y Tiziano ― con sus discípulos .

Nuestra hipótesis sin embargo es que la presencia de Ortiz en la ciudad en 1563 le impulsó a sustituir su rostro con el del maestro de Nápoles, dotando al cuadro en efecto de un mayor poder expresivo y simbólico así como de un nuevo artificio que no desestabilizaba en nada la intención manierista sino que la realzaba. Salvo por el hecho de relegar al olvido al buen Giorgione a cambio de fundir en un mismo grupo a músicos y pintores también al nivel de las Artes, lo que en realidad ya estaba haciendo con los pintores-músicos desde el comienzo .

Tanto el paralelismo entre Giorgione y Ortiz en su papel de primeras figuras en sus campos respectivos, como el hecho de que el primero había fallecido tempranamente 50 años antes, sin duda facilitaron la elección del pintor respecto de a qué figura debía sustituir Diego, estando todos los demás componentes vivos. De hecho era el viola-gambista más famoso en Europa, y activo en Nápoles, una de las Cortes más poderosas del momento.

En el “contexto musical” representado en el lienzo (un consort de violas con pintores-músicos amateurs) pero también en el contexto social de la época, el poder simbólico de un músico de prestigio era sin duda superior al de un pintor aún de los más renombrados. La Figura 9 muestra, entre los dos autorretratos conocidos de Giorgione, la silueta aproximada del rostro que ocupaba el lugar de Ortiz en el diseño original.

Como en el caso de Ortiz, existen en nuestra opinión un número similar de elementos gráficos similares o coincidentes entre ambos diseños ― a cuya comparación se pueden añadir igualmente los puntos 1 y 4 del Apartado 5 referidos al músico, junto con algunos de los escasos datos biográficos ya referidos a Giorgione: especialmente la leyenda consignada por Colbert que le incluía en el consort de violas ya incluso antes de la propuesta original de Boschini.

Figura 9. Autorretratos de Giorgione (invertidos) comparados con el rostro original. A: Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, Germany, ca. 1508. Inv. GG 454. B: Radiografía del rostro bajo el de Ortiz. Museo del Louvre (reproducida con permiso). C: Fine Arts Museum of Budapest, ca. 1508. Inv. Nº 86. D: Giorgione por Vasari (1568, p. 12).

Los rasgos faciales que creemos concurrentes son:

1) perfil pronunciadamente curvado de la nariz;2) tamaño y proporción de la nariz;3) boca pequeña de labios finos;4) comisura izquierda descendente;5) posición, forma y tamaño probables de las cejas (dado el ángulo diferente) ;6) cuencas oculares acusadas;7) arruga que desciende desde el lagrimal izquierdo;8) contorno del mentón y la barbilla;9) entrante de pelo en ángulo recto sobre la sien;10) contorno global de la cara;11) contorno global del cabello;12) aspecto general del rostro.

Son igualmente nuestras conjeturas:

(1) que el segundo anillo en el pulgar derecho de Tiziano pueda estar representando a su colega Giorgione omitido y ya fallecido ; y(2) que la leyenda del siglo XVII acerca de su presencia en el cuadro sólo puede provenir de quienes contemplaron la obra en sus comienzos, antes de ser finalizada. En tanto Colbert la menciona después de visitar el lienzo en su ubicación original, es probable que fuera informado allí mismo al respecto.

Figura 10. Silueta aproximada de Giorgione sosteniendo laúd en el diseño original.

7b. Citas. [localizables dentro de las notas]